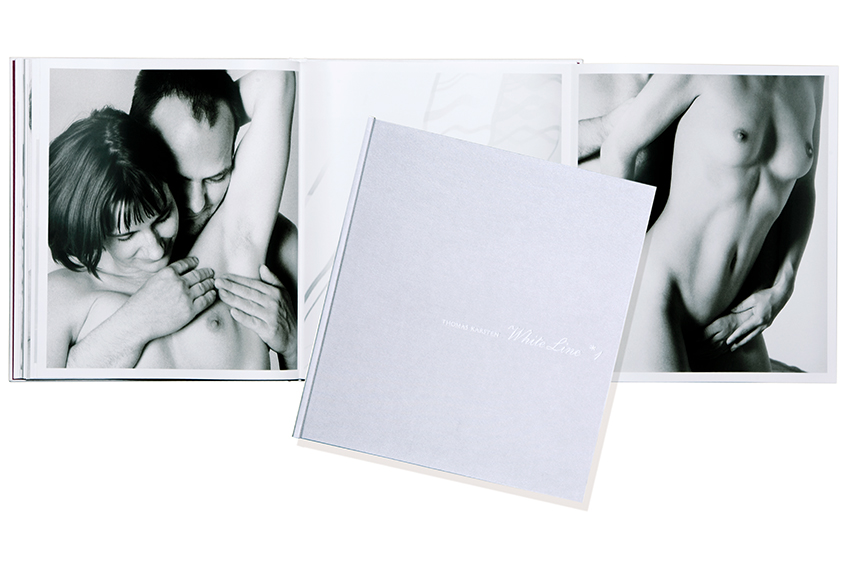

80 Seiten

78 Fotos + Graphiken

Großformat 30×34 cm + 5 Folder (90cm),

schweres Bilderdruckpapier,

schwarz/weiss (Triplex + Sonderfarbe + Lack)

Hardcover, weißer Leineneinband

Fotobuch mit Graphiken von Wolfgang Schultheiß

und einem Vorwort von Prof. John Wood

Signiert und nummeriert von Thomas

Texte: Deutsch und Englisch

Preis: 169,00 Euro

ISBN: 978-3-936165-39-5

Edition GALERIE VEVAIS, 2008

direkt hier bestellen: info@thomaskarsten.com

VORWORT:

von John Wood

Thomas Karsten und die Gabe der Freude

In einem der schönsten, leidenschaftlichsten und erotischsten Gedichte des letzten

Jahrhunderts schrieb der Dichter E. E. Cummings:

i like my body when it is with your

body. It is so quite a new thing.

Muscles better and nerves more.

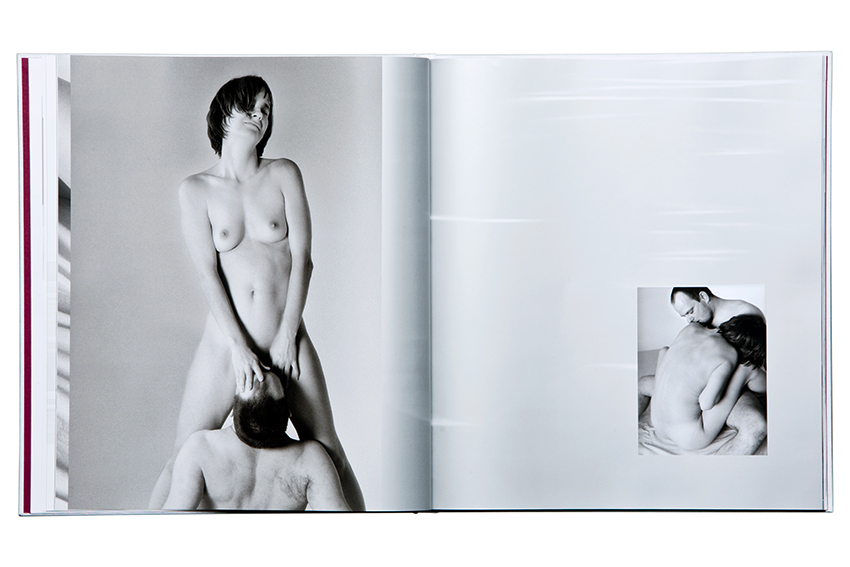

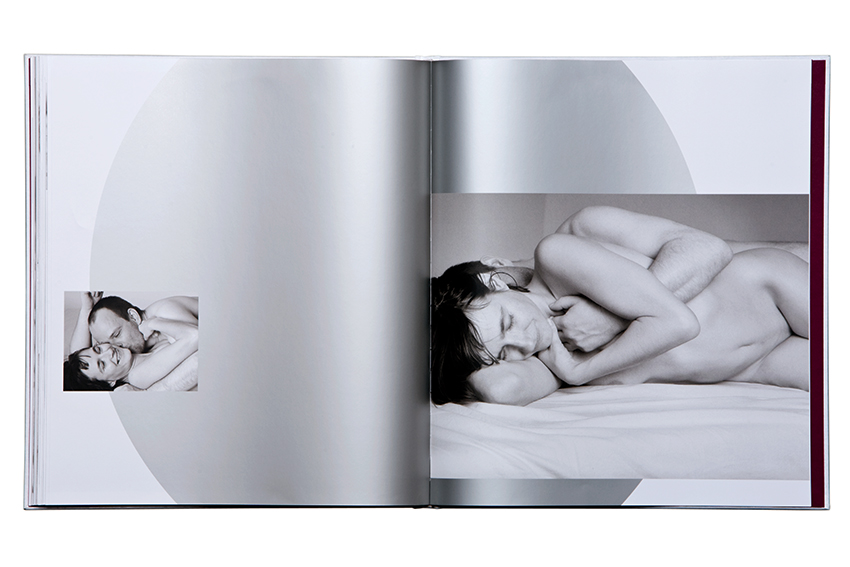

Diese Zeilen passen ausgezeichnet zum vorliegenden Band von Thomas Karsten mit den Fotos von Alexander und Babett, denn hier wie da geht es um Freude und Leidenschaft bei der Erotik.

Karsten ist ein großer Künstler, und die Erotik – die von keinem puritanischen Schamgefühl verfälschte, gesunde und natürliche Erotik – erklärt er beherzt zu seinem Hauptthema.

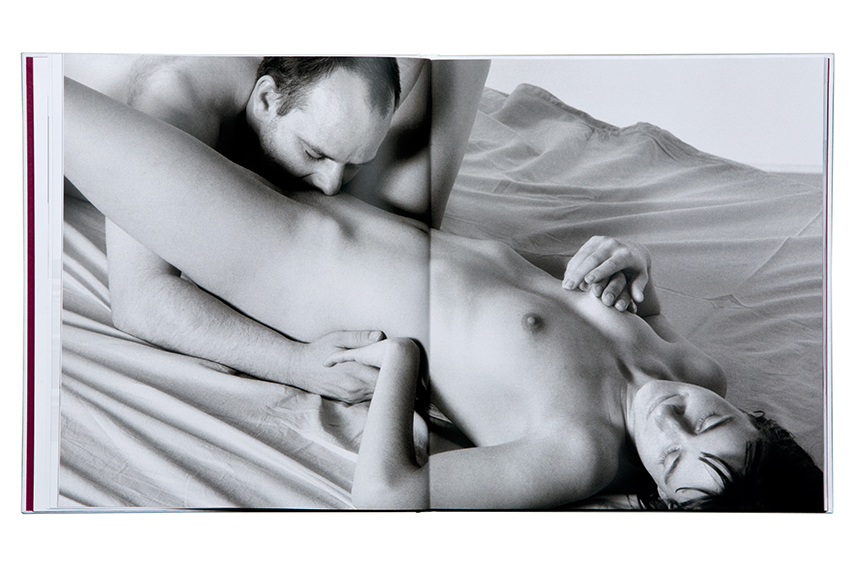

Genau wie auch Cummings verknüpft er die Würde einer erotischen Erfahrung mit deren sinnlichem Moment – hierzu betrachte man das Foto rechts, die quasi perfekte Aufnahme eines perfekten Augenblicks. Dies ist ein Bild, das das Zeug zumKlassiker hat, und zwar aufgrund der Zartheit, die es ausstrahlt (man beachte die Art und Weise, in der Babett ihren Arm um Alex legt) sowie dem überraschend neuartigen Arrangement, in dem das Bild komponiert ist. Das Foto kann als eine Illustration zu obenzitierten Versen interpretiert werden, die im Original zwar von einem männlichen Ich gesprochen, hier jedoch laut und deutlich von beiden Liebenden rezitiert werden. Cummings‘ Gedicht geht folgendermaßen weiter:

i like your body. i like what it does,

i like its hows. i like to feel the spine

of your body and its bones, and the tremblingfirm-

smoothness and which i will

again and again and again

kiss, i like kissing this and that of you,

i like, slowly stroking the, shocking fuzz

of your electric fur, and what-is-it comes

over parting flesh … And eyes big Love-crumbs,

and possibly i like the thrill

of under me you quite so new

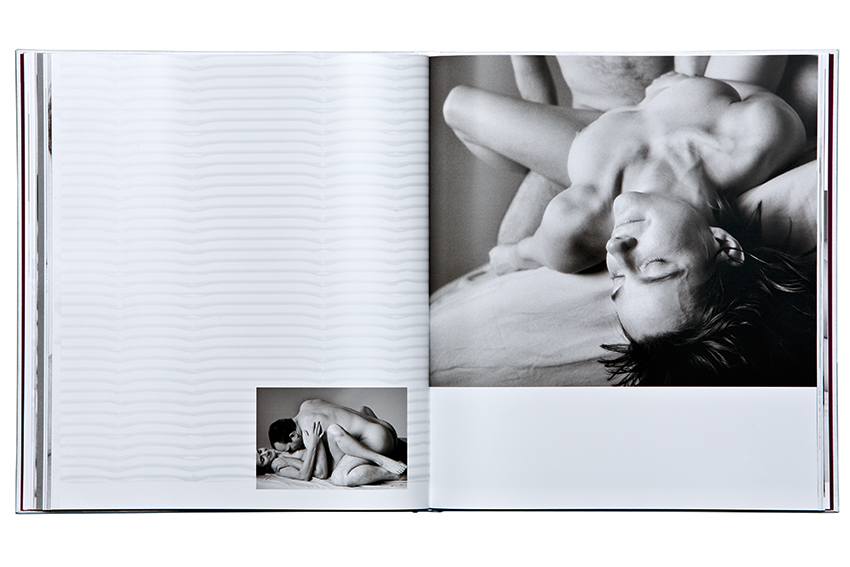

Alexander und Babett sind, genau wie Cummings und seine Frau Marion Morehouse, das berühmte Vogue-Mannequin, dem er auch seine Gedichte gewidmet hat, ein echtes Paar und nicht zwei für ein Fotoshooting gebuchte Modelle. An der genußvollen Art, wie sich die beiden vor der Kamera lieben, ist dies deutlich zu erkennen, als Beweis genügt bereits ein Foto: siehe oben. Und wieder wird das Bild untertitelt von E. E. Cummings’ Guter-Laune-Erotik:

may i feel said he

(i‘ll squeal said she

just once said he)

it‘s fun said she

(may i touch said he

how much said she

a lot said he)

why not said she

…

(cccome? said he

ummm said she)

you‘re divine! said he

(you are Mine said she)

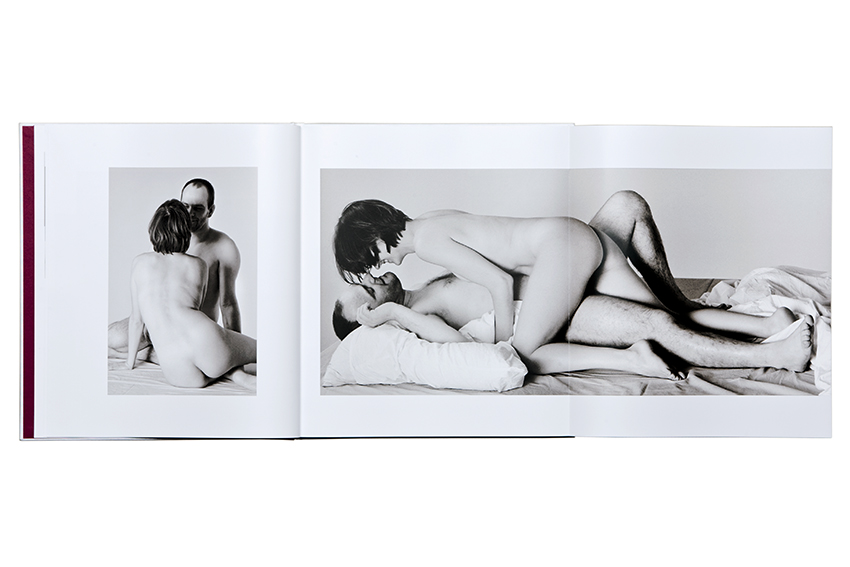

Das sind Liebende, die sich lachend und zufrieden einem reinen und göttlichen Hedonismus hingeben, welcher allein von den sexuellen Zwillingen Liebe und Begehren geschaffen wurde. So stellt man sich das wahre Eden vor: ohne jede Scham, nur erfüllt von Freude. Und kein anderer Fotograf kann diese paradiesischen Augenblicke besser einfangen als Thomas Karsten.

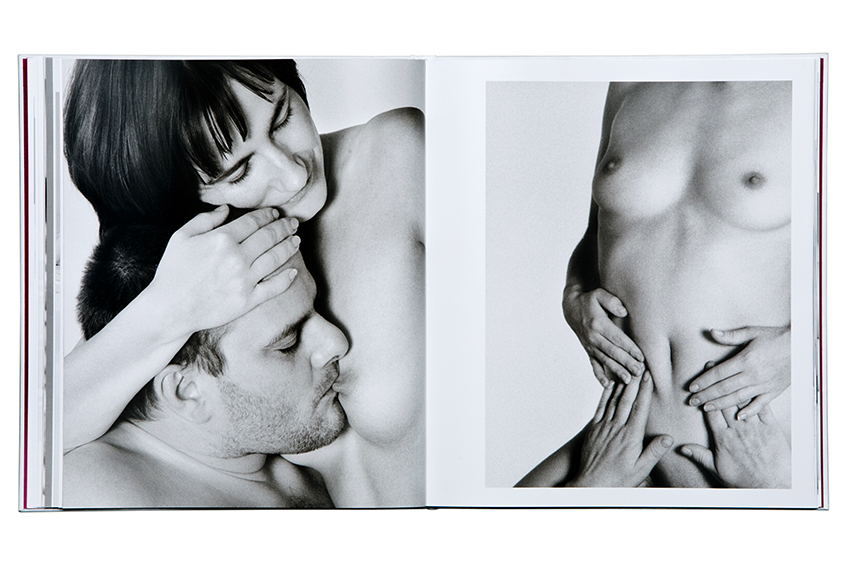

Diese seine Auffassung eines fröhlichen Garten Eden tritt auch in seinem verführerischen und wunderschönen Buch Days of Intimacy zutage, einer Sammlung der besten fotografischen Darstellungen von Weiblichkeit, die es gibt. Genau wie White Line ist auch Days of Intimacy ein äußerst erregendes Buch – ein Attribut, das eigentlich allen erotischen Bildbänden anhaften müßte, das aber genau betrachtet nur wenige aufweisen. Wenn man sich Thomas Karstens Bildbände ansieht, könnte man meinen, er habe es sich zum Ziel gesetzt, die Welt der Fotografie von steriler, unerregender Pseudo-Erotik zu reinigen. Und er befreit das Genre der erotischen Fotografie tatsächlich von seinen beiden Hauptmängeln: einerseits dem der kühlen Nacktheit, die »künstlerisch« wirken soll, aber in ihren asexuellen Posen nicht den geringsten Funken überspringen läßt, und andererseits dem der fetischistischen Darstellung von Erniedrigung und Beherrschung. Gemeinsam haben diese beiden Extreme eins: sie sind langweilig. Fotos, auf denen sich Nackte prügeln oder aufeinander urinieren, haben eine genauso limitierte Zielgruppe wie solche, die einem ungelenken Oben-ohne-Klischee frönen. Genau wie jede andere Kunst ist auch die erotische Kunst erst dann wirklich gut, wenn man sie wieder und wieder anschauen und sich in endloser Betrachtung verlieren kann. Das ist bei guter Musik genau dasselbe: man muß sie sich immer und immer wieder anhören, ganz egal wie oft. Oder gute Gedichte, deren Rhythmen und Metaphern sie uns lesen und wiederlesen lassen, bis wir sie auswendig können. Große Kunst erkennt man daran, daß sie zeitlos ist, stets frisch und stets aufs Neue belebend. Anders als Pornographie, die bei häufiger Betrachtung immer banaler wird und so den ständigen Nachschub von neuen Fotos notwendig macht, bleibt wahre erotische Kunst ästhetisch bestrickend und sexuell anregend, ganz egal, wie oft man sie sich zu Gemüte führt. Der erotische Moment, den man eingefangen hat, muß so glühend sein, daß sich das Feuer der Leidenschaft durch Zeit und Raum, ungeachtet der Umstände, bis zum Betrachter hindurchbrennt – dies ist z.B. bei Barberinis Faun der Fall, bei Rodins Iris, massagère des Dieux, einer ähnlichen weiblichen Faun-Skulptur, oder auch bei Rembrandts Radierungen, bei Courbets Origine du monde, bei den Aquarellen und Zeichnungen von Egon Schiele, bei Modigliani, Pascin, Balthus, Belmer und anderen Meistern der Erotik.

Thomas Karsten zelebriert Sinnlichkeit so, wie man sie zelebrieren muß, so, wie sie gesunde, integere Menschen seit Jahrhunderten zelebrieren. Wie Walt Whitman, einer der größten Dichter Amerikas, hat auch Karsten begriffen, daß:

Sex contains all, bodies, souls,

Meanings, proofs, purities, delicacies, results, promulgations,

Songs, commands, health, pride, the maternal mystery, the seminal milk,

All hopes, benefactions, bestowals, all the passions, loves, beauties,

delights of the earth,

All the governments, judges, gods, follow‘d persons of the earth,

These are contain‘d in sex as parts of itself and justifications of itself.

(from »A Woman Waits for Me«)

Anders ausgedrückt: Erotik begründet sich aus sich selbst, weil sie jeden einzelnen Aspekt unseres Lebens durchdringt und kräftigt. Hart Crane, ein weiterer Barde aus dem wahren Amerika (dem Amerika vor der Invasion durch Bush und seine talibanösen Bibelfundamentalistenhorden) sagte, »alles außer unserem Begehren« sei»falsch und lächerlich«.

Unser Begehren ist etwas, wodurch wir definiert werden, und deshalb sollte man sich seiner nicht schämen, weder in sexueller noch in erotischer Hinsicht. Ich kenne Alex und Babett persönlich, bin gut mit ihnen befreundet und habe ihnen erst kürzlich ein Geschenk zur Geburt ihrer kleinen Tochter geschickt; und wegen dieser Freundschaft ist es mir natürlich etwas peinlich zu sagen, wie antörnend ich ihre Fotos fand. Aber das muß gesagt werden; würde ihr sexuelles Begehren auf den Fotos mein sexuelles Begehren nicht genau so anstacheln, dann wären Karstens Fotos ungenügend, und Karsten hätte seine Pflicht als erotischer Künstler nicht erfüllt.

Das Schöne bei erotischer Kunst, besonders erotischer Fotografie, ist, daß sie – genau wie andere wahre Kunst auch – eine Gabe von Künstler und Modell an uns ist: gegeben werden die im Kunstwerk involvierten Gefühle. Dabei fungiert erotische Kunst zwar als Aphrodisiakum, aber niemals als Ersatz für Sex selbst, genausowenig wie William Blakes Prophetische Bücher ein Ersatz für eigene spirituelle Erfahrungen sind. Beide Kunstwerke sind emotionale Gaben; das eine regt den Geist an, das andere die anderen Teile.

Wenn wir zum Beispiel ein Gedicht von William Butler Yeats lesen, uns ein Gemälde von Caspar David Friedrich ansehen oder eine Symphonie von Gustav Mahler anhören, dann wollen wir dabei dasselbe fühlen, was der Künstler bei Erschaffung des Kunstwerks fühlte – wir erwarten, daß die Kunst frühere Gefühle wieder aufleben läßt und sie quer durch Zeit und Raum zu uns zu transferieren imstande ist. Kunst ist eine Möglichkeit, um mehr vom Leben zu haben. Kunst ist eine Gabe des Lebens selbst, denn durch sie können wir unser eigenes Leben mit den kreativsten Lebensaugenblicken von Karsten, Blake, Friedrich, Mahler, Yeats und vielen anderen bereichern sowie auch denen derer, die bei den visuellen Kunstwerken Modell saßen.

Sieht man sich Schieles Arbeiten an, seine Modelle, wie sie da sitzen, Beine auseinander, um dem Betrachter freie Sicht zu ermöglichen, oder auch die lächelnde Frau in Die Traum-Beschaute, die ihre Schamlippen aufspreizt, damit man noch besser sieht, dann wird einem klar, daß diese Modelle aktiv beteiligt waren an der Fabrikation der emotionalen Beigaben des Kunstwerks, die in diesem Fall erotische Beigaben sind. Der Fotograf ist verantwortlich für die ästhetische Dimension der Bilder, es obliegt seiner Entscheidung, welche emotionalen Augenblicke er hervorhebt und welche nicht, aber die Modelle, hier Alex und Babett, tragen durch ihre Leidenschaft und durch ihr Begehren wesentlich zur emotionalen Verfeinerung des Kunstwerkes bei.

Erotische Kunst ist daher die am reichhaltigsten gebende aller visuellen Künste. Ein normalerweise privater Augenblick, der sich sonst hinter verschlossenen Türen abspielt und für öffentliche Blicke nicht zugänglich ist, wird von Künstler und Modell in einem Projekt des gemeinsamen Einvernehmens geschaffen und für andere geöffnet. Das Reizvolle liegt dabei natürlich auch in diesem Augenblick selbst – zuschauen bei »dieser Sache« wollten wohl schon unsere ältesten Vorfahren. Voyeurismus ist im Grunde eine genauso natürliche Regung wie sein nächster Verwandter, der Klatsch. Wir genießen es, intime Details aus dem Leben anderer Leute zu erfahren – warum sonst sind Boulevardgazetten die auf der ganzen Welt am häufigsten verkauften Presseerzeugnisse? Je intimer die Details, desto größer die Nachfrage, desto höher die Auflage. Das ist ein genauso elementarer Vorgang der Natur wie der Geschlechtsverkehr selbst. Was ein Künstler sich preiszugeben entschließt, ist das, was ihm selbst nicht unangenehm ist. Rousseau konnte zu seinen schlimmsten Fehlern und privatesten Geheimnissen stehen und Dinge erzählen, die anderen wohl schwer fallen würden; Yeats sprach offen von seiner im Alter zwar schwindenden Potenz, aber durchaus noch vorhandenen sexuellen Lust; Musil stand zu seinem gelegentlichen Verlangen nach Qual, Céline zu seiner Menschenverachtung, Dostojewski zu seiner Schuld. Künstler sind eben, Gott sei Dank, verschieden, und somit wird unser Leben, wenn wir uns mit Kunst befassen, bereichert von denjenigen Aspekten der Persönlichkeit des Künstlers, die er mitzuteilen gewillt ist oder war. Wir genießen Karstens Kunst – mit Alex’ und Babetts Beitrag – genauso, wie wir auch die Kunst von Rousseau oder Dostojewski genießen. Jeder offenbart das, was es ihn zu offenbaren drängt, so meisterhaft er kann, und der ehemals private, intime Moment wird durch unser stilles Lesen, Betrachten und Nachdenken trotz der Veröffentlichung wieder zum Privatvergnügen.

Die Gabe der Erotik ist dabei die intimste aller künstlerischen Gaben, und selten wird sie wirklich vollkommen erreicht, wenn dies auch sehr oft versucht wird. In der Geschichte des Abendlandes war Erotik der am häufigsten verdrängte und am heftigsten bekämpfte kulturelle Beigeschmack, was hauptsächlich in der ungesunden Feindseligkeit von Judentum, Christentum und Islam dem sinnlichen Vergnügen gegenüber begründet ist beziehungsweise in der Unfähigkeit dieser drei Schwesterreligionen, das Körperliche einfach zu akzeptieren und zu genießen, wie es ist. Nicht erst seit dem Ende des klassischen Altertums gibt es in den Städten Mauerkunst, die erigierte Penisse darstellt, um die herum die schönen Worte Hic Habitat Felicitas (Hier wohnt die Freude) geschrieben stehen. Der Sieg jener drei strengen, verstaubten Religionen ersetzte das berauschende Lebensambrosia durch trockenes, zähes Manna.

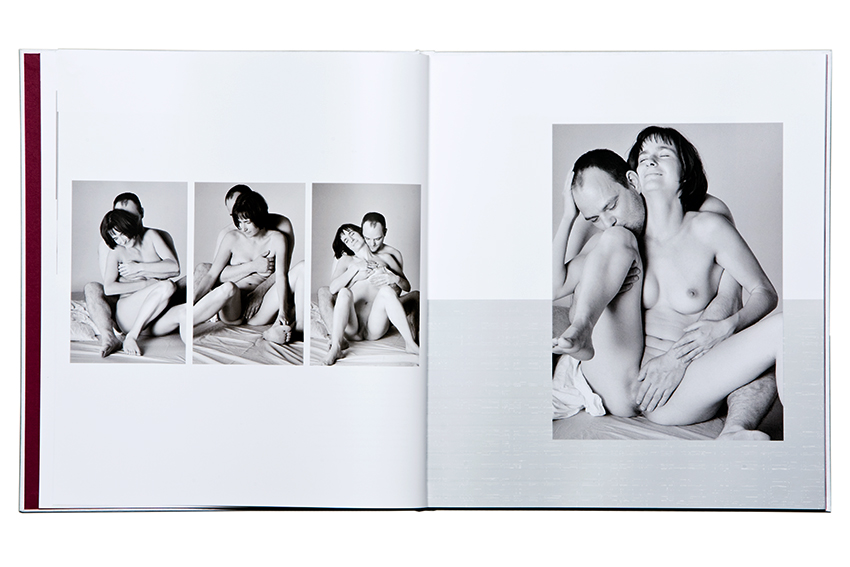

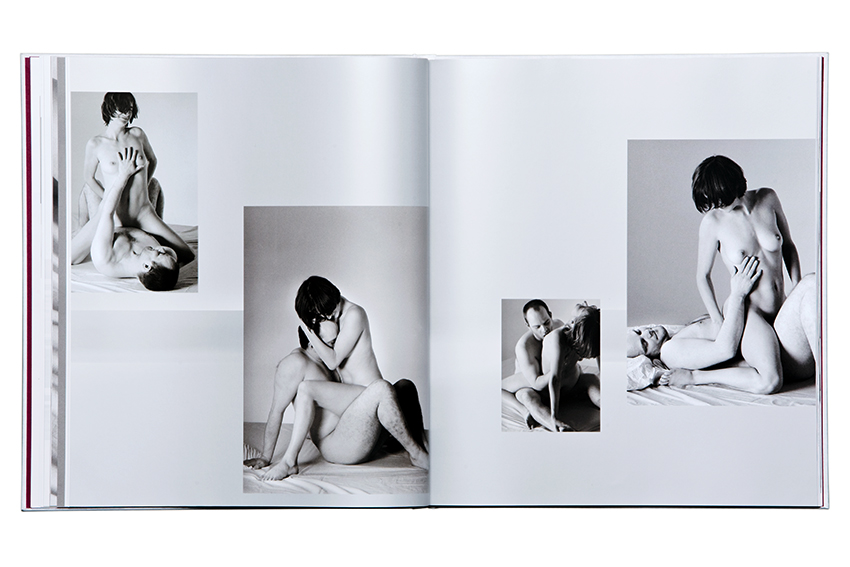

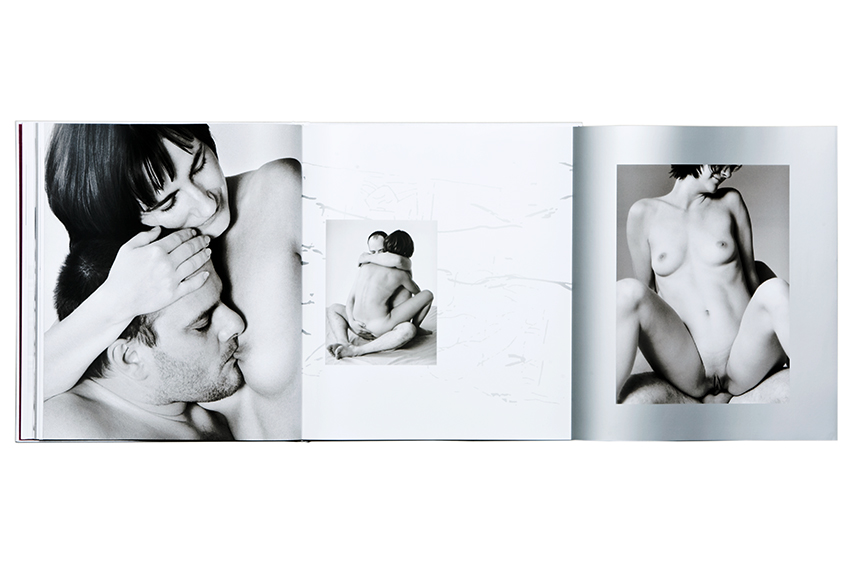

Die Einwohner von Karstens künstlerischer Welt aber ernähren sich noch immer von Ambrosia und definieren sich nach den alten, griechisch-klassischen Maßstäben; hierzu möge man den Triptychon (siehe links) betrachten. Karsten kann nicht nur das spielerische Begehren seiner Modelle gut rüberbringen, sondern auch – und das ist ja die eigentliche Aufgabe eines Kunstfotografen – die bildhauerische Dichte und Komplexität des Arrangements. Den Winkel und die Beleuchtung, die er hier wählt, verwandeln Babetts Körper in Marmor, aber einen höchst geschmeidigen und zarten Marmor. Ihre Hand langt hinter ihrem Rücken nach Alex, und zusammen zerfließen sie zu einer klassisch gemeißelten Skulptur, zu einer Skulptur von Venus und Mars, diesen beiden mächtigen Liebenden, die Cupido das Leben schenkten. DasTriptychon ist ebenso monumental

– und wieder kommen einem Verse von Walt Whitman in den Sinn:

–

Love-thoughts, love-juice, love-odor, love-yielding, love-climbers, and the climbing sap,

Arms and hands of love, lips of love, phallic thumb of love, breast of love, bellies press‘d and glued together with love,

Earth of chaste love, life that is only life after love,

The body of my love, the body of the woman I love, the body of the man, the body of the earth.

(from »Spontaneous Me«)

Und Gaia, die Erdenmutter, der »Körper der Erde«, der geheiligte, lebende, atmende, Leben spendende, von sexueller Vitalität strotzende Planet selbst ist es, der die Erotik mit ergreifender Klarheit und Selbstsicherheit zelebriert.

Und immer noch gibt es in den Fotos von White Line mehr zu entdecken.

Wer sich in die Bilder vertieft, merkt schnell, daß sich das abgebildete Paar nicht nur körperlich nahe steht, sondern daß die Nähe auch hier tiefer hinab reicht. Und wieder kann man eine passende Bilduntertitelung in E. E. Cummings’ Lyrik finden. In einem relativ bekannten Gedicht für Marion schrieb er:

i carry your heart with me (i carry it in

my heart) i am never without it (anywhere

i go you go, my dear; and whatever is done

by only me is your doing, my darling)

i fear

no fate (for you are my fate, my sweet) i want

no world (for beautiful you are my world, my true)

and it‘s you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that‘s keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)

Die Wurzel der Wurzel, der Samen des Samens, der Himmel des Himmels über einem sogenannten »freien« Leben – das ist es, was Thomas Karstens White Line uns im Endeffekt sagen will. Das Buch ist ein Fest zur Verehrung des Lebensbaumes, jenes geheiligten und gesegneten Baumes, von dessen Früchten keine einzige verboten ist. ˜

ENGLISCH

Thomas Karsten and the gift of joy

In one of the previous century’s most joyful, passionate, and erotic poems, poet E. E. Cummings wrote:

i like my body when it is with your

body. It is so quite a new thing.

Muscles better and nerves more.

It is a poem which reflects that same joyful, passionate, and erotic spirit of Thomas Karsten’s photographs of Alex and Babett. Karsten is a great artist whoboldly takes eroticism as his theme – healthy, natural, human eroticism untrammeled by puritanical shame. He is an artist who like Cummings communicat as the dignity of the erotic experience along with its sensuous thrill. Look at the photo on the right, a perfect photograph of a perfect instant. It is an image sure to become a classic because of its tenderness (note how Babett’s arm goes around Alex) and its surprising, totally original composition and cropping. It could be an illustration of those very lines of poetry, which in the poem are spoken by a male voice, but here are clearly, loudly spoken by both lovers. Cummings’ poem continues:

i like your body. i like what it does,

i like its hows. i like to feel the spine

of your body and its bones, and the tremblingfirm-

smoothness and which i will

again and again and again

kiss, i like kissing this and that of you,

i like, slowly stroking the, shocking fuzz

of your electric fur, and what-is-it comes

over parting flesh … And eyes big Love-crumbs,

and possibly i like the thrill

of under me you quite so new

Alex and Babett, like Cummings and Marion Morehouse, Cummings’ wife and a famous Vogue model, to whom he dedicated his poetry, are also a couple, not two models employed for a photo-shoot. And that can easily be seen in the joyful play of their love-making. One need only consider one of these photographs to realize that: the photo above. One again thinks of Cummings’ good-humored eroticism:

may i feel said he

(i‘ll squeal said she

just once said he)

it‘s fun said she

(may i touch said he

how much said she

a lot said he)

why not said she

…

(cccome? said he

ummm said she)

you‘re divine! said he

(you are Mine said she)

These smiling, happy lovers have given themselves over to a pure and sacred hedonism born from love and lust, the sexual Gemini. This is Eden, the real Eden, where there is no shame – only joy. And no other erotic photographer could have so caught that Edenic moment as Thomas Karsten has.

That same sense of a paradise with fun is evident in his seductive and beautiful book Days of Intimacy, one of the greatest photographic celebrations of femininity that has been recorded. Like White Line it is an arousing book, as any book of erotic photographs should be, but as few, in truth, actually are. Looking at Karsten’s books, one would think that he set it as his task to cleanse the photographic world of unarousing pseudo-eroticism. Karsten rescues erotic photography from the extremes of bland nudes in clichéd, sexless poses that stirs not the slightest thrill to those equally boring fetishistic images of humiliation and domination – fisting to being urinated upon – images with as limited an audience as that for the bland, sexless nudes. Erotic art, like any other visual art, is only good if it pulls us back again and again to gaze, to wonder, and to consider. Ist power is the same as that of great music which demands we listen again an again, no matter how many times we already have, or great poetry whose melodies and metaphors make us read, reread, and then read again. The mark of great art is that it is forever fresh and forever rewarding. Unlike pornography, which can lose its erotic charge upon subsequent viewings and necessitate the need for fresh, new examples, true erotic art, regardless of how often it is viewed, remains aesthetically compelling and sexually stimulating. The captured erotic instant must be so caught that the fire of passion burns through time and circumstance – just as it does in the Barberini Faun or Rodin’s similar fauness, Iris, massagère des Dieux, in Rembrandt’s etchings, in Courbet’s Origine du monde, the watercolors and drawings of Schiele, in Modigliani, Pascin, Balthus, Belmer, and other masters of the erotic. Thomas Karsten celebrates the sexual as it should be celebrated, as healthy men and women have always celebrated it. Karsten like Walt Whitman, America’s great poet, understands that:

Sex contains all, bodies, souls,

Meanings, proofs, purities, delicacies, results, promulgations,

Songs, commands, health, pride, the maternal mystery, the seminal milk,

All hopes, benefactions, bestowals, all the passions, loves, beauties,

delights of the earth,

All the governments, judges, gods, follow‘d persons of the earth,

These are contain‘d in sex as parts of itself and justifications of itself.

(from »A Woman Waits for Me«)

In other words, the erotic is its own justification because it permeates and invigorates every aspect of our lives. Hart Crane, another singer of the authentic America, America before it and the Presidency were hijacked by a minority of Taliban-like Christian fundamentalists, wrote that »all else« but our »lusts« are »a fake and mockery«.

Our lusts define us, and there should be no shame in them, in sex, or in the erotic. I know Babett and Alex personally, am friends of theirs, and just recently sent them a gift for their new baby daughter. Because of our friendship, it makes me somewhat uncomfortable to say how sexually stimulating I found their photographs. But if I were not able to say that, were not able to tell them that their lust stirred my lust, then Karsten’s photographs would have been a failure, and Karsten would not have met his duty as an erotic artist.

Part of the joy of erotic art, especially erotic photography, is that it – again like all the other arts – is a gift to us from the artist and the model, a gift of the emotion inherent in it. Even though erotic art can be an aphrodisiac, it is never meant to be a substitute for sex, any more so than William Blake’s Prophetic Books are meant to be a substitute for actual spiritual experience. Both are emotional gifts, one meant to stimulate spiritual contemplation, the other sexual contemplation.

For example, when we look at a Caspar David Friedrich painting, we do so in order to feel the emotion he felt, just as we listen to a symphony by Mahler or read a poem by Yeats in order to have their emotion recreated and transmitted to us across time. Art is a way for us to have more Life. It is the gift of life itself, for it allows us to absorb into our lives the most essential creative moments of the lives of Karsten, Blake, Friedrich, Mahler, Yeats, and others – and all the visual artists’ models, as well.

When we look at Schiele’s work, at his models with their legs opened for the viewer’s eyes, or the smiling model in Die Traume-Beschaute who has spread her labia apart so that we might even more clearly see her, we can be assured these models were active partners in the creation of the works’ emotional gifts, which in those cases were erotic gifts. Karsten alone shaped the aesthetic dimension of his photographs and chose to capture and frame certain emotional moments while rejecting others, but part of his work’s gift to the viewer was also shaped by Babett and Alex, by their passions and desires.

Erotic art, then, is clearly the most generous of the visual arts. Artist and model jointly agree to create and share with others a moment that is usually private, hidden from view, a moment that exits behind closed doors. But it is also the kind of moment, which probably from the beginning of humanity, other people have always wanted to witness. Voyeurism is just as natural to our species as its closest cousin, gossip. We love knowing the private lives of others; why else are tabloids a world-wide, billion dollar business? The more private the detail, the more curious we are to know it, and this seems as basic to our nature as sex itself. Artists choose to share what they feel comfortable sharing. Rousseau could admit to his most despicable deeds and personal secrets, things which would have embarrassed others to admit, just as Yeats could share the frustrations of an old man’s still vibrant lusts but waning vitality, and Musil his casual acceptance of cruelty, or Céline his misanthropy, or Dostoyevsky his guilt. Fortunately all artists are not alike, and so our lives are enriched by whatever aspects of their personalities they have felt or feel they could share. We take delight in Karsten’s art – and Babett’s and Alex’s contribution – just as we do in Rousseau’s or Dostoyevsky’s. Each masterfully communicates what he was driven to say, and each is a private pleasure in the solitude of our reading, viewing, and contemplation.

However, those most private of artistic gifts – the erotic ones – are always the rarest and often the most desired. In the West they have historically been the most denied and the most railed against because of the unhealthy and debilitating hostility of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam to pleasure and to the senses – or at least those three sister religions’ inability to openly acknowledge and delight in the physical. Not since the loss of the classical world has one been able to find urban wall-sculpture depicting erect penises around which are written the joyful words Hic Habitat Felicitas (Here Lives Happiness). The triumph of those three austere, desert religions substituted the intoxicating ambrosia of life for a dry, unleavened manna.

The inhabitants of Thomas Karsten’s artistic world still feed on ambrosia and are classically defined. Consider the triptych photographs left above. Karsten can obviously communicate the playfulness and desire of the bodies he is photographing, but like any other fine arts photographer, he can also convey their sculptural depth and density. His angle and lighting here turn Babett’s body into marble, but marble of the most supple and tender quality. Her hand reaches behind her for Alex, and together they are transformed into a piece of classical sculpture, transformed into Venus and Mars, those two equal and powerful lovers who gave birth to Cupid. Also consider the equally sculptural triptych photographs right below. It again brings to mind the poetry of Walt Whitman:

Love-thoughts, love-juice, love-odor, love-yielding, love-climbers, and the climbing sap,

Arms and hands of love, lips of love, phallic thumb of love, breast of love, bellies press‘d and glued together with love,

Earth of chaste love, life that is only life after love,

The body of my love, the body of the woman I love, the body of the man, the body of the earth.

(from »Spontaneous Me«)

And it is »the body of the earth«, Gaia, the sacred, living, breathing, procreating, sexually abounding planet herself that the erotic most assuredly and most touchingly celebrates.

Yet there is still more in these White Line photographs.

In reading these photographs, anyone can see that this couple is not merely physically intimate; there is something deeper here, as well. Again, it is something one also finds reflected in the love poetry of E. E. Cummings. In a well-known poem to Marion, he wrote:

i carry your heart with me (i carry it in

my heart) i am never without it (anywhere

i go you go, my dear; and whatever is done

by only me is your doing, my darling)

i fear

no fate (for you are my fate, my sweet) i want

no world (for beautiful you are my world, my true)

and it‘s you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life; which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that‘s keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart (i carry it in my heart)

The root of the root, the bud of the bud, the sky of the sky of a tree called life – that is finally the meaning of Thomas Karsten’s White Line. It is the celebration and the adoration of that sacred, blessed tree called Life, the tree from which no fruit is ever forbidden. ˜