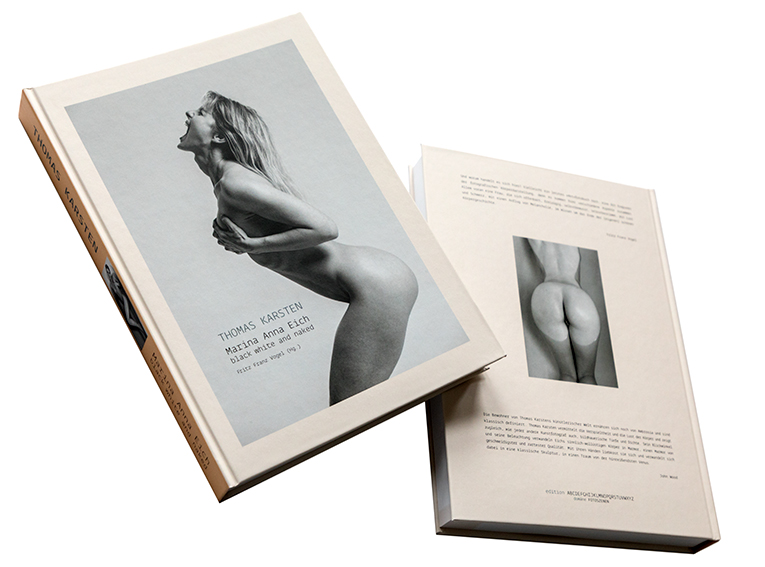

ca. 300 Seiten

ca. 200 Abbildungen

Format 21×30 cm,

170g schweres Kunstdruckpapier,

SW (alles 4 farbig CMYK)

Hardcover

Fotobuch mit verschiedenen Texten

Texte: Deutsch, Englisch

Preis: 85,00 Euro

ISBN: 978-3-03858-511-4

edition ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, 2017

Hier direkt bestellen: info@thomaskarsten.com

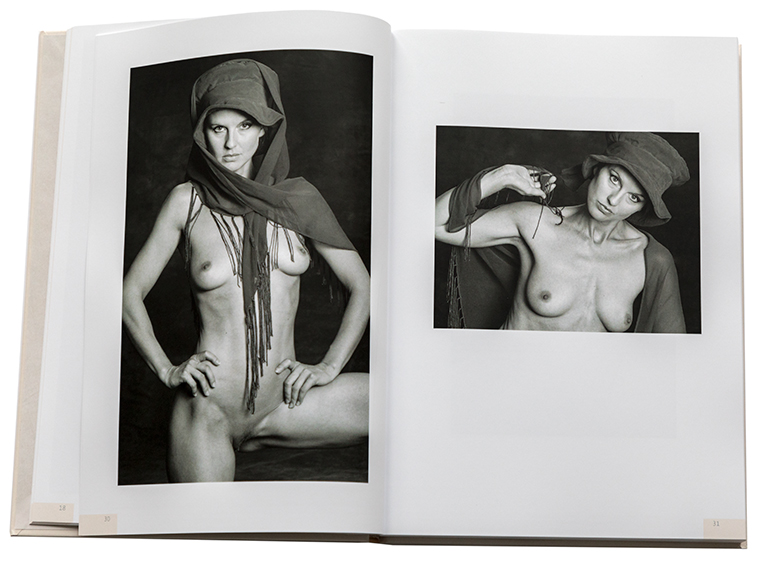

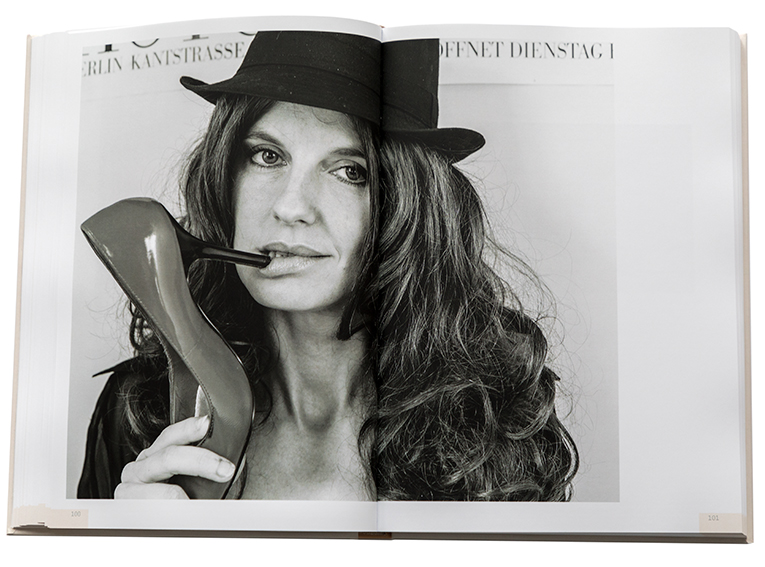

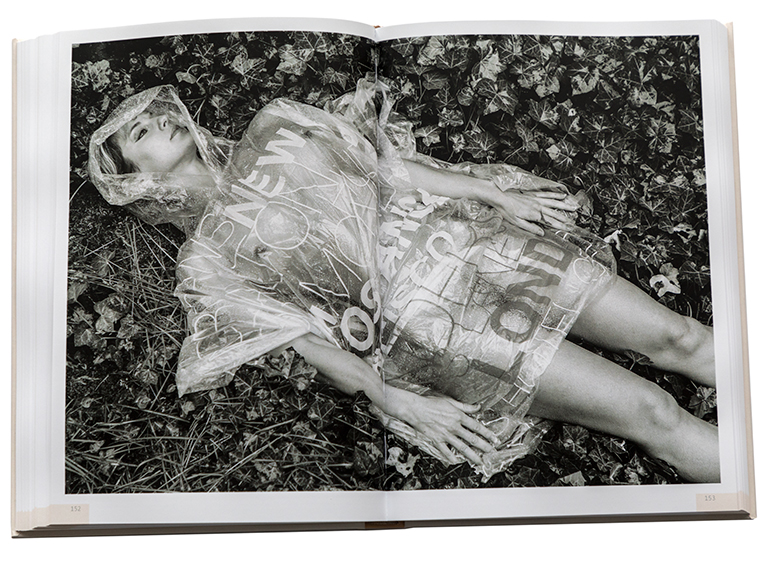

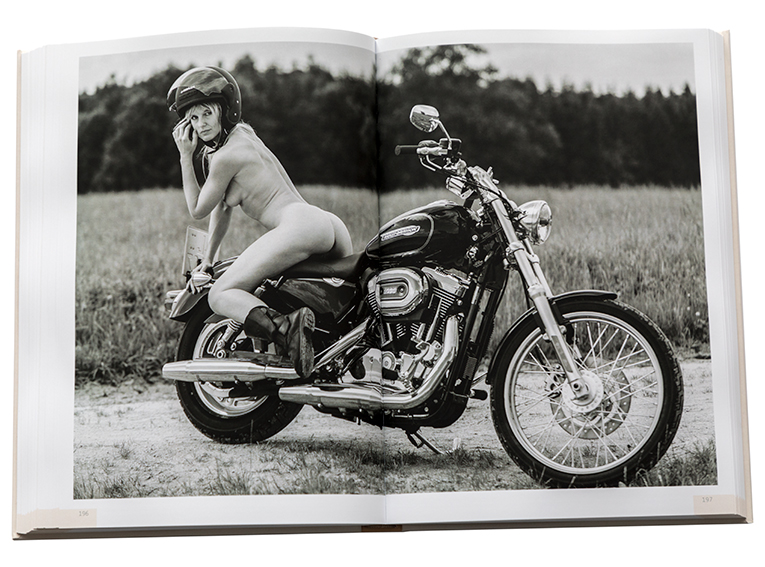

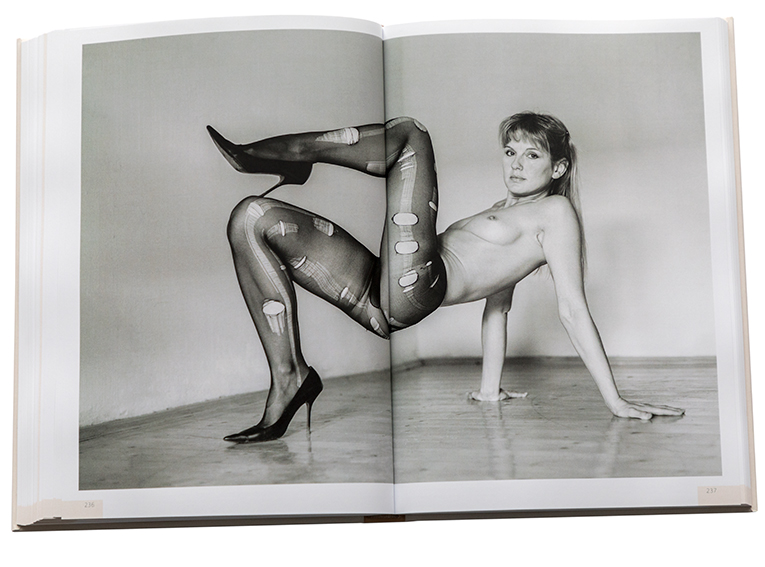

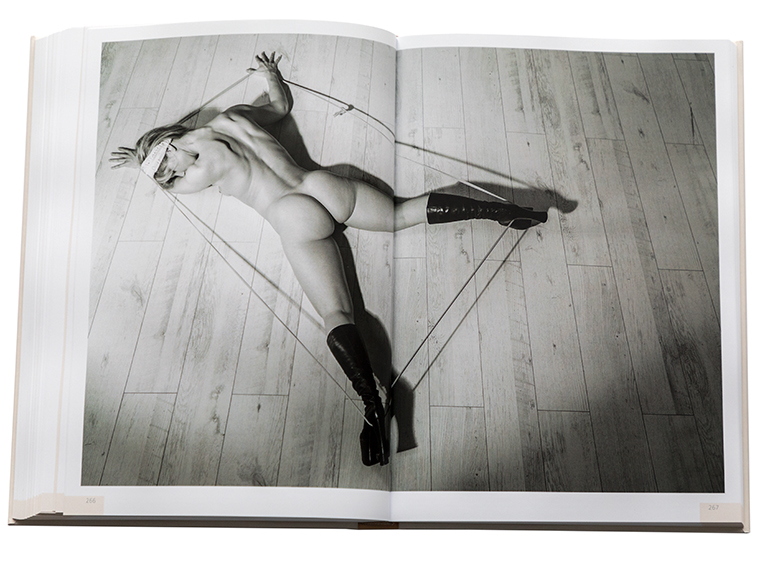

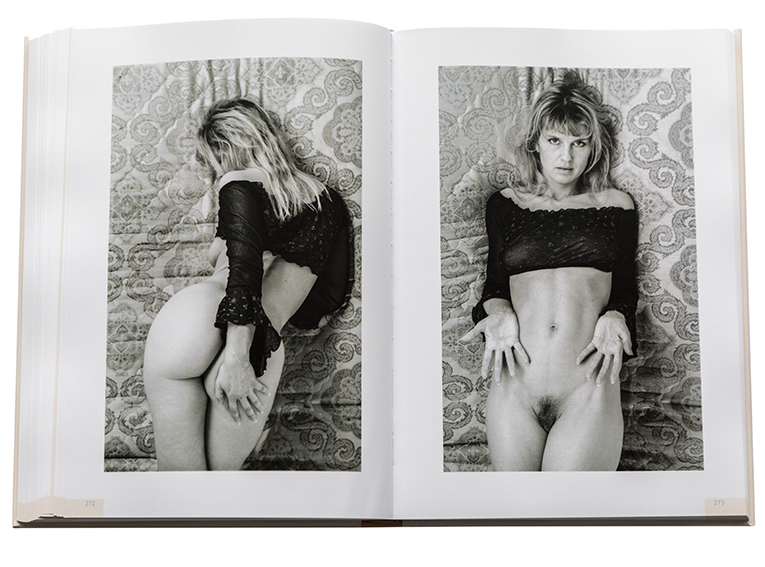

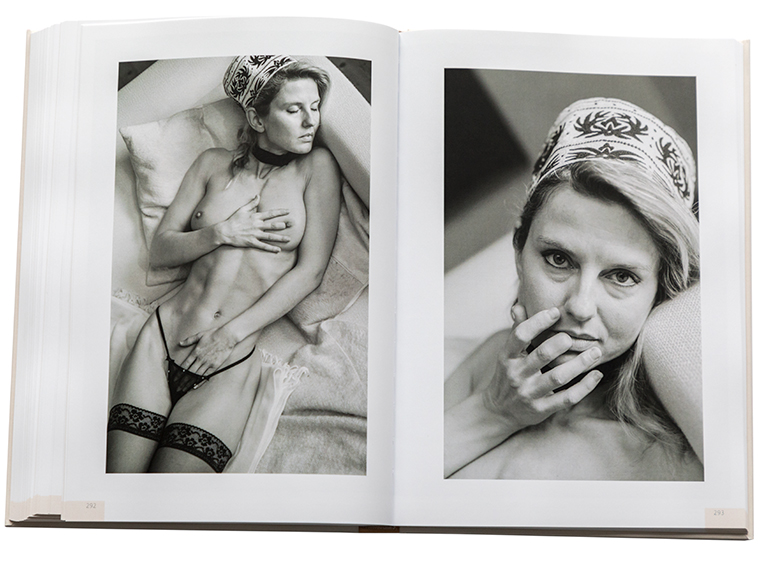

Black, White, and Naked is Thomas Karsten’s second volume devoted to German actress, Marina Anna Eich. In 2014 he published Marina Anna Eich: An Erotic Portrait. This first work was shot in full color. This newer book, like the title suggests is all black & white, featuring 240 photos. And it’s a beautiful portrait of a most alluring woman. Marina is known as a film actress and producer in her country. She is also a linguist and a classically trained ballet dancer. Video clips and interviews highlight her gentle, intelligent nature and a sweet, feminine demeanor. In contrast, when modeling for Karsten, she unleashes her inner siren – gorgeous, confident, and unabashedly sexual.

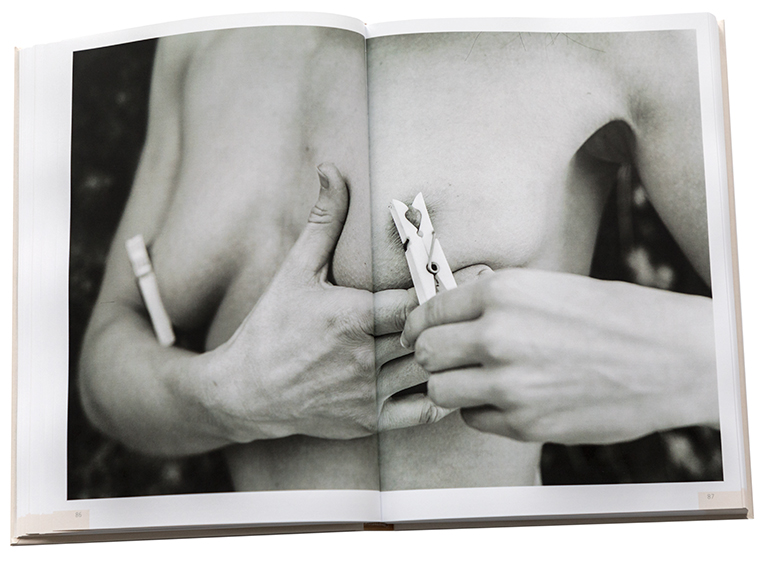

Tall and blonde with a dancer’s exquisite, supremely fit form, Marina is a natural before the camera. She is a commanding presence. And Karsten’s black & white photography is the perfect compliment to her daring acts within Black, White, and Naked. The monotone format subdues what might be overwhelming in color and accentuates the glorious, seemingly perfect form that is Marina. Karsten goes everywhere – there are close ups of Marina fingering her vagina, probing her anus, masturbating with dildos, peeing in the snow, and more. Together they are fearless. They are also perfect – both Karsten’s compositions and Marina’s flawless, exquisite form are breathtaking. And its inspiring.

Photographers dream of discovering a muse like Marina; models dream of being discovered by such a capable visionary as Thomas Karsten. This new volume, like its predecessor, showcases the magic that can happen when two perfect souls find each other. Black, White, and Naked exemplifies what high-end, artistic erotica looks like.

Michelle7-Erotica.com

THOMAS KARSTEN AND MARINA ANNA EICH: THE GIFT OF JOY

by

John Wood

In “Thomas Karsten and the Gift of Joy,” the introduction to his book

White Line, I wrote that “Karsten is a great artist who boldly takes eroticism as his theme—healthy, natural, human eroticism untrammeled by puritanical shame. He is an artist who like poets Walt Whitman and E. E. Cummings communicated the dignity of the erotic experience along with its sensuous thrill.” 1 In one of the previous century’s most joyful, passionate, and erotic poems, poet E. E. Cummings wrote,

I like my body when it is with your

body. It is so quite a new thing.

Muscles better and nerves more.

i like your body. i like what it does,

. . . i like kissing this and that of you,

This poem reflects that same joyful, passionate, and erotic spirit of Thomas Karsten’s photographs. Erotic art, like any other visual art, is only good if it pulls us back again and again to gaze, to wonder, and to consider. Its power is the same as that of great music which demands we listen again and again, no matter how many times we already have, or great poetry whose melodies and metaphors make us read, reread, and then read again.

The mark of great art is that it is forever fresh and forever rewarding. Unlike pornography, which can lose its erotic charge upon subsequent viewings and necessitate the need for fresh, new examples, true erotic art, regardless of how often it is viewed, remains aesthetically compelling and sexually stimulating. The captured erotic instant must be so caught that the fire of passion burns through time and circumstance—just as it does in the Barberini Faun or Rodin’s similar fauness, Iris, messagère des Dieux, in Rembrandt’s etchings, in Courbet’s L’Origine du monde, the watercolors and drawings of Schiele, in Modigliani, Pascin, Balthus, Belmer, and other masters of the erotic.

Karsten’s newest work, a book of pure, sacred, and erotic hedonism, is a celebration of the sensuousness and beauty of Marina Anna Eich, one of the world’s most alluring women and one of Germany’s great film stars. Karsten’s book is truly a celebration of the original Garden of Eden, the one the great English mystic poet William Blake wrote of in his poetry, a fragrant, lush garden wrecked by a “jealous” deity more interested in mindless obedience and slavery than in independence and joy—the two necessities for a full and complete life.

Here is Eden, the real Eden, where there is no shame—only the labors of joy and pleasure. No other erotic photographer has ever so caught that Edenic moment as Thomas Karsten has. That same sense of a paradise blended with simple joy and frolicksom fun is evident in all his books. Looking at his work, one would think that he set it as his task to cleanse the photographic world of unarousing pseudo-eroticism. Karsten rescues erotic photography from its two equally boring polar opposites: bland nudes in “arty,” sexless poses that stir not the slightest thrill and extreme fetishistic images of humiliation and domination. Erotic art, as I said, is like any other visual art. It is only good if it pulls us back again and again to gaze, to wonder, and to consider the magical gift before our eyes.

Thomas Karsten celebrates the sexual as it should be celebrated, as healthy men and women have always celebrated it. Like America’s greatest poet Walt Whitman, Karsten understands that

Sex contains all, bodies, souls,

Meanings, proofs, purities, delicacies, results, promulgations,

Songs, commands, health, pride, the maternal mystery, the seminal milk,

All hopes, benefactions, bestowals, all the passions, loves, beauties, delights of the earth,

All the governments, judges, gods, follow’d persons of the earth,

These are contain’d in sex as parts of itself and justifications of itself.

(from “A Woman Waits for Me”)

In other words, the erotic is its own justification because it permeates and invigorates every aspect of our lives. Hart Crane, another great poet and singer of the authentic America before it was hijacked by the xenophobes and religious fundamentalists, wrote that “all else” but our “lusts” are “a fake and mockery.” Our lusts define us, and there should be no shame in them, in sex, or in the erotic.

Part of the joy of erotic art, especially erotic photography, is that it—again like all the other arts—is a gift to us from the artist and the model, a gift of the emotion inherent in it. Even though erotic art can be an aphrodisiac, it is never meant to be a substitute for sex, any more so than Blake’s Prophetic Books are meant to be a substitute for actual spiritual experience. Both are emotional gifts, one meant to stimulate spiritual contemplation, the other sexual contemplation. When we look at a painting by Caspar David Friedrich or Arnold Böcklin, we do so in order to feel the emotion they felt, just as we listen to a symphony by Mahler or read a poem by Yeats in order to have their emotion recreated and transmitted to us across time. Art is a way for us to have more Life. It is the gift of life itself, for it allows us to absorb into our lives the most essential creative moments of the lives of Blake, Friedrich, Böcklin, Mahler, Yeats, Karsten, and others—but not forgetting those of the visual artists’ models.

When we look at Egon Schiele’s work, for example, at his models with their legs opened for the viewer’s eyes, or the smiling model in Die Traume-Beschaute who has spread her labia apart so that we might even more clearly see her, we can be assured these models were active partners in the creation of the works’ emotional gifts, which in those cases were erotic gifts. Karsten shaped the aesthetic dimension of his photographs and chose to capture and frame certain emotional moments while rejecting others, but part of his work’s gift to the viewer was also shaped by Marina Anna Eich, one of Germany’s leading film stars, a producer, and a linguist. Erotic art, then, is clearly the most generous of the visual arts. Artist and model jointly agree to create and share with others a moment that is usually private, hidden from view, a moment that exists behind closed doors. But it is also the kind of moment which, probably from the beginning of humanity, other people have always wanted to witness. Voyeurism is as natural to our species as is sex. We love knowing the private lives of others. The more private, the more personal the details, the more curious we are to know them. I asked Marina Anna Eich about her experience of working with Karsten. She told me she “did enjoy the project as Thomas has this skill to catch sensuality and nudity in such a nativeness. At some point I didn’t even realize that he was still there being so positively distanced and with a lot of discretion.”

Artists choose to share what they feel comfortable sharing. Rousseau could admit to despicable deeds and personal secrets, things which would have embarrassed others to reveal, just as Yeats could share the frustrations of an old man’s still vibrant lusts but waning vitality, and Musil his casual acceptance of cruelty, or Céline his conflicting anti-Semitism and kindness, or Dostoyevsky his guilt. Fortunately all artists and all models are not alike, and so our lives are enriched by whatever aspects of their personalities they have felt they could share. We take delight in Karsten’s art—and Marina Anna Eich’s generous participation in it—just as we do in the collaboration of any artist and his or her model. Each masterfully communicates what she or he was driven to say, and the result is an aesthetic, psychological, or erotic pleasure—and often a combination of the three, as we see in Eich’s and Karsten’s emotionally rich collaboration.

However, those most private of artistic gifts—the erotic ones—are always the rarest and often the most desired. In the West they have historically been the most denied and the most railed against because of the unhealthy and debilitating hostility of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam to pleasure and to the senses—or at least those three sister religions’ inability to openly acknowledge and delight in the physical. Not since the loss of the classical world has one been able to find urban wall-sculpture depicting erect penises around which is written the joyful Latin expression Hic Habitat Felicitas (Here Lives Happiness.) The triumph of those three austere, desert religions substituted the intoxicating ambrosia of life for a dry, choking, unleavened manna.

The inhabitants of Thomas Karsten’s artistic world still feed on ambrosia and are classically defined. Karsten obviously communicates the playfulness and desire of the bodies he is photographing, but like any other fine arts photographer, he also conveys their sculptural depth and density. His angle and lighting here turn Eich’s voluptuous body into marble, but marble of the most supple and tender quality. Her hands caress herself and transform her into classical sculpture, into a dream of the most rapturous Venus. And again she and Karsten evoke the poetry both of Whitman and Cummings.

In „Spontaneous Me“ Whitman wrote:

Love-thoughts, love-juice, love-odor, love-yielding, love-climbers, and the climbing sap,

Arms and hands of love, lips of love, phallic thumb of love, breast of love, bellies press’d

and glued together with love,

Earth of chaste love, life that is only life after love,

The body of my love, the body of the woman I love, the body of the man,

the body of the earth.

What Karsten so clearly understands about the nude is a quality both John Berger and Kenneth Clark equally understood and described.

To render the nude properly one must know the “alphabet of love,” as John Berger put it in his essay on Modigliani. “Everything begins with the skin, the flesh, the surface of the body, the envelope of the soul,” Berger wrote. And he continued to say, “Whether the body is naked or clothed . . . makes little difference. Whether a body is male or female makes no difference. All that makes a difference is whether the painter [or the photographer, I would add] had, or had not, crossed that frontier of imaginary intimacy on the far side of which a vertiginous tenderness begins. Everything begins with the skin and what outlines it. And everything is completed there too.”2

And as Kenneth Clark famously stated, “No nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling, even if it be only the faintest shadow—and if it does not do so it is bad art and false morals.”3

It is “the body of the earth,” it is Gaia, the sacred, living, breathing, procreating, sexually abounding planet herself that the erotic most assuredly and most touchingly celebrates.

Yet there is still more in these photographs, a quality that is so often missing from most “erotic photography” and “erotic literature”—and that is the sheer, unadulterated sense of fun, of joy, and of play—those qualities that give eros so much of its definition. Eich and Karsten were both obviously having fun in making these photographs, which was a three year project. Their pleasure is as evident as any receptive viewer’s must also be.

“The root of the root, the bud of the bud, the sky of the sky of a tree called life,” as Cummings put it—that is finally the meaning of Thomas Karsten’s art. It is the celebration and adoration of that sacred, blessed tree called Life, the tree from which no fruit is ever forbidden.

Notes

1. White Line, photographs by Thomas Karsten (Vevais, Germany: Edition

Galerie Vevais, 2006, deluxe portfolio edition ; Edition Galerie Vevais, 2008, regular edition). Several passages or variants of them from White Line also appear in this essay.

2. John Berger, “Modigliani’s Alphabet of Love,” in John Berger Selected Essays, ed.

Geoff Dyer (New York: Pantheon Books, 2001), 391.

3. Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form (New York: Pantheon Books, 1956), 17.

Author’s Note:

John Wood is an American poet and art critic. He co-curated the Smithsonian Institution/National Museum of American Art exhibition Secrets of the Dark Chamber, the catalogue of which was a New York Times Book Review Book of the Year. He holds a Ph.D. in English literature and held the Pinnacle Professorship in Liberal Arts at McNeese University, where he directed the MFA program in Creative Writing and Graduate Studies in English for thirty years. In addition to holding a professorship in English literature, he also held a professorship in photographic history. He has frequently given lectures at Harvard and many museums including the Museu Nacional d’Art de Cataluyna (Barcelona), where his subject was the neglected field of Spanish Pictorial Photography. He is Editor of 21st Editions, a fine arts photographic press in the U.S., and a co-editor of Edition Galerie Vevais in Germany. His books of criticism as well as his books of poetry have won a variety of awards including the 2009 Gold Deutscher Fotobuchpreis. He has published books on Flor Garduño, Sally Mann, Eikoh Hosoe, Wouter Deruytter,

Brigitte Carnochan, four on Joel-Peter Witkin, including Witkin’s journals, which he edited, and many other photographers. He has a book forthcoming from EGV jointly written with Harvard poet and art critic Steven Brown on Spanish painter Dino Valls.